Robots to Play a Crucial Role in Future Foxconn Expansion

by Peter Schnall & Erin Wigger

Foxconn is planning to add one million robots to its workforce within the next three years. This is alarming news for those concerned about China’s working class citizens. Foxconn has been growing at an enormous pace and has doubled its workforce over the last few years and is now ranked third largest employer in the world. They are faced with rising labor costs which they have attempted to address through increased productivity of its workforce and also by expanding west to China’s Chengdu province – home to a still large population of poor agricultural workers and a new source of inexpensive, unorganized labor.

News reports have been appearing in the press for the past five years about Foxconn workers’ struggle for higher wages and better working conditions. Few gains were made by workers however until 2010, when Foxconn received a large amount of bad publicity due to the suicides of 11 of its workers. The sensationalism of the story was due in part to the collective and public nature of the suicides (which involved workers in similar fashion leaping to their death from the roof of Foxconn buildings), paired with the fact that Foxconn’s Shenzhen plant is the major manufacturing headquarters of the popular Apple iPhone and IPad.

Foxconn responded to the public outcry resulting from these deaths by raising the salary of its workers and installing netting around the roofs of its buildings to forestall further suicides. They also required workers to sign a “no suicide” clause in their work contract, which prevents their families from receiving a death benefit.

But Foxconns’ dilemma hasn’t been resolved. As its work force continues to swell so does the threat of organized worker activities. (Of course, Foxconn workers like all other workers in China are represented by an official Chinese Union answerable to the Chinese government and which fails to represent the interests of workers in almost every case. But the threat of organized resistance poses a serious problem for Foxconn: how to continue increasing productivity while lowering costs in a competitive economy.

With pressure to produce still more coming from Apple and other end users and the company complaining of low profit margins, Foxconn has now sought to increase its production processes by means of robotics. According to Terry Gou, the company’s founder and chairman, Foxconn already makes use of some 10,000 robots and sees many benefits in expanding its use of robots. Gou plans to use the new robots to perform tasks such as spraying, welding and assembling. He projects that utilizing up to 1 million robots will improve the working conditions at his plant for Foxconn workers by eliminating those parts of the production process which are repetitive and menial, effectively elevating it’s workforce into positions with increased skill-level and value.

But will the modernization of Foxconn’s plants into a futuristic, automated factory actually mean better working conditions for China’s workers, or just a loss of jobs? Gou’s argument seems to favor the hypothesis of Skill Biased Technological Change (SBTC), which purports to positively favor a shift from an un-skilled labor force to skilled workers. SBTC has, however, become the center of debate on the unequal distribution of power in the workplace (management vs. workers) and the increasing inequality of wealth between social classes in Capitalist societies.

How can Foxconn reduce costs if they hire robots unless their “employment” is accompanied by the layoff of workers (workers being the most expensive part of the production process)?

Despite Gou’s words to the contrary, workers at Foxconn’s plants remain skeptical. Tania Branigan of The Guardian reports that some workers question whether Gou’s announcement was sincere. “I am suspicious,” said Liu Kaiming, of the Institute of Contemporary Observation, which supports workers in Guangdong, “Machines can do it, but think about the cost … overall, workers are still much cheaper. This is probably just for sensational effect, [to] put pressure on workers.”

And it is difficult to imagine that the small and hard-won improvements workers have fought for at Foxconn are not under attack. In essence, how can workers complain of labor practices which cause them to feel like machines – enforced silence on the production line, short or non-existent breaks, etc – when the company can literally replace them with robots capable of working 24-hours a day without complaint?

In the long run, replacing humans with robots seems a dead-end process. After all, robots are unlikely candidates to purchase the products of their own labors. Without a well-paid labor force capitalism lacks a market for its goods. This problem is a flashback to the issues raised by Jeremy Rifkin in 1995 in his book “The End of Work: The decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era” in which he argued that many jobs are never coming back and that we should prepare for a world without work. Of course, the emergence of China and the employment of millions there has been the major argument against his thesis. More on this in a later entry…

Globalization, Foxconn and the Chinese working people. What is the problem?

by Peter Schnall and Erin Wigger

We begin herein a series of blogs looking at the relationship between the processes of globalization and the worldwide development of industrial production as they impact on work organization and affect the lives of working men and women. Central to this exploration will be an in depth look at Foxconn, one of China’s foremost companies, which we will use as an example of issues related to globalization. China has one of the fastest growing economies in the world and has become over the past several decades one of the most powerful countries in the world. While China has always been rich in natural resources, the secret to its success is not a product of its agricultural production or natural resources, but it’s immense population which provides a large, well-trained and inexpensive (relative to the Western world) workforce..

Of China’s many rapidly growing companies, one stands out from the rest; among the Fortune Global 500 with $102 billion in revenue in 2010 and now with almost 1 million workers, Foxconn and it’s parent company Hon Hai have set the standard which many other companies now follow. Founded in 1974 by Terry Gou (currently Chairman and President), the Taiwanese company set out to provide businesses with alternatives to more expensive electronics manufacturing. According to the Foxconn Global website, Foxconn has achieved remarkable sales and growth figures. Between 2009 and 2010 the company’s consolidated revenues grew 52.98% to NT$2.997 trillion (US$104.6 billion) (CNA English News).

Now the largest electronics manufacturing company in the world and the fifth largest company worldwide in number of employees after Walmart, China National Petroleum, State Grid, & the U.S. Postal Service – Foxconn supplies companies such as Apple, Dell, Hewlett-Packard and Sony with notebooks, desktop computers, monitors, smart phones, iPads and other popular products. “Foxconn has 13 mainland factories in nine cities in China. Planned factories include expanding sites at Chengdu in Sichuan province, Wuhan in Hubei province, and Zhengzhou in Henan province.” (Wikipedia) The first of these plants was its Shenzhen plant, which opened in 1988. Since then, it has become Foxconn’s largest plant, a walled city of more than 1.15 square miles including 15 factories, its own fire department, worker dormitories and a small city of restaurants and shops, all located on one property.

Although the plant is responsible for a large portion of the company’s overall success, it has also been the subject of repeated reports of worker mistreatment. It was in the news repeatedly last year after it experienced a number of suicides – 14 to date. Foxconn responded to the suicides by raising wages 66%, boosting its number of counselors, and making stress management programs available to workers. It also built safety netting around its factory to prevent further suicide attempts and, for a short while, asked its workers to sign an anti-suicide pact. Foxconn has also responded to the suicides at the plant with claims it’s number of suicides, per capita, are not much higher than China’s national average, implying the suicides are not really a problem.

Suicides and employee discontent at the Shenzhen plant are not the only problems facing Foxconn. Foxconn has also been accused of discrimination against main-land Chinese workers and the forcing of many rural farmers off their land to make way for the huge factory developments currently heading farther and farther inland. Foxconn’s Chengdu plant is one of these. You might have already heard of the Chengdu plant; it appeared in the news last month after three workers were killed in an explosion caused by inadequately ventilated combustible dust. Built in the rural southwestern province of Sichuan, Chengdu was rapidly converted into a facility to make iPads in response to high demand from Apple. Currently staffed by 80,000 workers, Foxconn is looking to add another 220,000 workers at the Chengdu facility in coming years.

The cluster of suicides, the explosion at Chengdu, and the long-standing complaints by workers raise serious questions for some. Why did this group of young workers commit suicide? Did Foxconn’s work environment and employee policies play a role in these deaths? What are the labor practices at Foxconn? Is there a connection between Foxconn’s rapid growth, its labor practices and the explosion at Chengdu? Many newspapers and watch-dog groups such as SACOM (Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehavior) have charged the company with “dangerous working environment, inadequate measures on work safety, excessive and forced overtime work, and that workers are deprived of a social life.” Can these accusations be substantiated and what is Foxconn’s defense?

In subsequent blogs we will look at these issues regarding Foxconn. And beyond Foxconn, we need to ask if these problems are limited to Foxconn or are these issues typical of China? Finally, we want to raise the question about the relationship between these working conditions in Chinese factories and the overall process of globalization? Stayed tuned for subsequent blogs, the first of which will examine what is publicly known about working conditions at the Shenzhen plant.

Robots to Play Crucial Role in Foxconn Future Expansion

With pressure to produce still more coming from Apple and other end users and the company complaining of low profit margins, Foxconn has now sought to increase its production processes by means of robotics. According to Terry Gou, the company’s founder and chairman, Foxconn already makes use of some 10,000 robots and sees many benefits in expanding its use of robots. Gou plans to use the new robots to perform tasks such as spraying, welding and assembling. He projects that utilizing up to 1 million robots will improve the working conditions at his plant for Foxconn workers by eliminating those parts of the production process which are repetitive and menial, effectively elevating it’s workforce into positions with increased skill-level and value.

But will the modernization of Foxconn’s plants into a futuristic, automated factory actually mean better working conditions for China’s workers, or just a loss of jobs? Gou’s argument seems to favor the hypothesis of Skill Biased Technological Change (SBTC), which purports to positively favor a shift from an un-skilled labor force to skilled workers. SBTC has, however, become the center of debate on the unequal distribution of power in the workplace (management vs. workers) and the increasing inequality of wealth between social classes in Capitalist societies.

Organizational Justice

A SHORT DEFINITION by Muntaner:

“Organizational justice refers to whether or not decision- making procedures are consistently applied, correctable, ethical, and include input from affected parties (procedural justice). It also refers to respectful, considerate and fair treatment of people by supervisors (relational justice).26

Organizational justice research has been developed from equity theory,27 which considers the ratio of input and output, and compares that proportion with those of referent others. If this comparison leads a worker to believe that his or her situation is inequitable, the worker is motivated to reduce that inequity by reducing input, increasing output or changing the referent others.

These personal assessments are reinforced by strong social norms about fairness. Research has shown that perceived justice is associated with people’s feelings and behaviors in social interactions, and that low organizational justice is an important psychosocial predictor of employees’ health in modern workplaces.28 For example, evaluations of low justice have been related to negative emotional reactions,29 which in turn have been associated with unhealthy patterns of cardiovascular and immunological responses and certain health problems.30″

From: C Muntaner, J Benach, W C Hadden, D Gimeno and F G Benavides, A glossary for the social epidemiology of work organisation: Part 1, Terms from social psychology, J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006;60;914-916 doi:10.1136/jech.2004.032631

ADDITIONALLY…

In a Finnish study of metal factory workers examining the relationship between work stress and the risk of death from cardiovascular disease using the the effort-reward imbalance model (as well as the job strain model), those reporting low supervisor support were 64% more likely to develop heart disease over 25 years.

The study followed 812 employees from 1973 – 2001. Increased risks were seen after adjusting for age, gender, standard risk factors such as cholesterol, high blood pressure, and smoking, and job strain and effort-reward imbalance. The study positively concluded that high job strain and effort-reward imbalance seem to increase the risk of cardiovascular mortality.

26 Kivimaki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, et al. Association between organizational inequity and incidence of psychiatric disorders in female employees. Psychol Med 2003;33:319–26.

27 Adams JS. Inequity in social exchange. In: Berkowitz L, eds. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol 2. New York: Academic Press,1965;267–99.

28 Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Vahtera J. Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health 2002;92:105–8.

29 Weiss HM, Suckow K, Cropanzano R. Effects of justice conditions on discrete emotions. J Appl Psychol 1999;84:786–94.

30 Beehr TA. Psychological stress in the workplace. London: Routledge, 1995.

Introduction to Work-Related Stressors

“Work, so fundamental to basic survival and health, as well as to wealth, well-being, and positive social identity, has its darker and more costly side too.1 Work can negatively affect our health, an impact that goes well beyond the usual counts of injuries, accidents, and illnesses from exposure to toxic chemicals. The ways in which work is organized—particularly its pace, intensity and the space it allows or does not allow for control over one’s work process and for realizing a sense of self-efficacy, justice, and employment security—can be as toxic or benign to the health of workers over time as the chemicals they breathe in the workplace air. Certain ways in which work is organized have been found to be detrimental to mental and physical health and overall well-being, causing depression and burnout [1-2], as well as contributing to a range of serious and chronic physical health conditions, such as musculoskeletal disorders, hypertension, chronic back pain, heart disease, stroke, Type II diabetes, and even death [3-5]. Accordingly, many occupational health scientists refer to these particularly noxious characteristics of work as hazards or risk factors of the psychosocial work environment to which employees are exposed.”

Work-Related Psychosocial Stressors

“Researchers have thought about and measured work stressors in various ways over the last 30 years [54-57]. The most highly studied type of work stressor is “job strain,” that is, work which combines high psychological job demands with low job decision latitude or job control [11]. A more recently developed and important way of describing job stress is “effort-reward imbalance,” a “mismatch between high workload (high demand) and low control over long-term rewards” [58, p. 1128]. Low reward includes low “esteem reward” (respect and support), low income, and low “status control” (poor promotion prospects, employment insecurity, and status inconsistency). Another stressor, “organizational injustice,” has been defined in three ways: a) distributive injustice—is one unfairly rewarded at work?; b) procedural injustice—do decision-making procedures at work fail to provide for input from affected parties, useful feedback, and the possibility of appeal, and are they not applied fairly, consistently, and without bias?; c) relational injustice— do supervisors fail to treat workers with fairness, politeness, and consideration [59]? In addition, research studies have examined “threat-avoidant” vigilant work, i.e., work that involves continuously maintaining a high level of vigilance in order to avoid disaster, such as loss of human life [56]. This is a feature of a number of occupations at high risk for CVD, e.g., truck drivers, air traffic controllers, and sea pilots. More recently, researchers have been investigating the health effects of employment insecurity and “downsizing” [60].”

1. Rugulies, R., U. Bultmann, B. Aust, and H. Burr, Psychosocial Work Environment and Incidence of Severe Depressive Symptoms: Prospective Findings from a 5-Year Follow-up of the Danish Work Environment Cohort Study, American Journal of Epidemiology, 163:10, pp. 877-887, 2006.

2. Rafferty, Y., R. Friend, and P. Landsbergis, The Association between Job Skill Discretion, Decision Authority and Burnout, Work and Stress, 15:1, pp. 73-85, 2001.

3. Belkic, K., P. Landsbergis, P. Schnall, and D. Baker, Is Job Strain a Major Source of Cardiovascular Disease Risk?, Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health, 30:2, pp. 85-128, 2004.

4. Krause, N., D. R. Ragland, B. A. Greiner, S. L. Syme, and J. M. Fisher, Psychosocial Job Factors Associated with Back and Neck Pain in Public Transit Operators, Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health, 23:3, pp. 179-186, 1997.

5. Krause, N. and D. R. Ragland, Occupational Disability Due to Low Back Pain: A New Interdiscipline Classification Based on a Phase Model of Disability, Spine, 19:9, pp. 1011-1020, 1994.

54. Schnall, P. L., P. A. Landsbergis, and D. Baker, Job Strain and Cardiovascular Disease, Annual Review of Public Health, 15, pp. 381-411, 1994.

55. Kristensen, T. S., M. Kronitzer, and L. Alfedsson, Social Factors, Work, Stress and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention, The European Heart Network, Brussels, Belgium, 1998.

56. Belkic, K., P. A. Landsbergis, P. Schnall, et al., Psychosocial Factors: Review of the Empirical Data among Men, in The Workplace and Cardiovascular Disease Occupational Medicine: State of the Art Reviews, Schnall, P., K. Belkic, P. A. Landsbergis, and D. Baker (eds.), Hanley and Belfus, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 24-46, 2000.

57. Belkic, K., P. Landsbergis, P. Schnall, and D. Baker, Is Job Strain a Major Source of Cardiovascular Disease Risk?, Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health, 30:2, pp. 85-128, 2004.

58. Siegrist, J., R. Peter, A. Junge, P. Cremer, and D. Seidel, Low Status Control, High Effort at Work and Ischemic Heart Disease: Prospective Evidence from Blue Collar Men, Social Science and Medicine, 31, pp. 1127-1134, 1990.

59. Kivimaki, M., M. Virtanen, M. Elovainio, A. Kouvonen, A. Vaananen, and J. Vahtera, Work Stress in the Etiology of Coronary Heart Disease—A Meta-Analysis, Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health, 32:6(Special Issue), pp. 431-442, 2006.

Taken from: Schnall PL, Dobson M, Rosskam E, Editors Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences, Cures. Baywood Publishing, 2009.

Threat Avoidant Vigilance

THREAT-VOIDANT VIGILANT WORK

“Research studies have examined “threat-avoidant” vigilant work, i.e., work that involves continuously maintaining a high level of vigilance in order to avoid disaster, such as loss of human life [56]. This is a feature of a number of occupations at high risk for CVD, e.g., truck drivers, air traffic controllers, and sea pilots. More recently, researchers have been investigating the health effects of employment insecurity and “downsizing” [60].” (Taken from: Schnall PL, Dobson M, Rosskam E, Editors Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences, Cures. Baywood Publishing, 2009.)

A cross-sectional study of San Francisco MUNI bus drivers conducted to evaluate the prevalence of hypertension in 1500 black and white male bus drivers (as compared to employed individuals in general) found that, after adjusting for age and race, hypertension rates for bus drivers were significantly greater than rates for each of the three comparison groups (individuals from a national survey, a local health survey and individuals undergoing baseline health examinations prior to employment as bus drivers).

Karen Belkic developed a Professional-Driver specific Occupational Stress Index in an effort to capture some of the effects of the work environment on drivers. She emphasizes that, “when the potential consequences of one’s actions can include disaster, work can become a threat-avoidant vigilant activity…. There is epidemiologic, human laboratory and experimental animal data that directly and indirectly links prolonged exposure to threat-avoidant vigilant activity with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including cardiac electrical instability and even sudden cardiac death (Corley 1977, Lown 1990, Menotti 1985, Murphy 1991, Suurnakki 1987, Theorell 1993).”

The OSI Questionnaire for professional drivers is about half the length of the General OSI, and the questions are very concrete and germane to this occupational group.

Below are a few select items from the OSI for professional drivers:

16. Do you always have at least one break during your work day? Yes No

If yes, how many breaks do you usually have?_______

How long is your usual break?___________

17. The times at which you drive / your work schedule:

*Do you have a regular work schedule? Yes No

*If yes, when do you begin work? _____________ End work:________________

* Do you drive the split shift (early morning and afternoon rush hours)

a. Yes, I constantly work the split shift

b. Sometimes

c. Rarely or never

*Do you drive in the dark/at night ?

a. No, I work (drive) only during the daylight hours.

b. Yes, I drive in the city at night, and/or when it’s dark.

c. Yes, I drive inter-city (long routes) at night, and/or when it’s dark.

(If no, continue with question 18)

*If you drive on the job at night,

Are the roads well lit? Yes No

Are the roads divided according to the direction of traffic? Yes No

*Do you drive after midnight (third/night shift)? Yes No

If yes, do you drive the night shift:

a. Constantly

b. On a rotating basis (describe please how this rotates:______________)

19. Do you perform heavy lifting at work?

a. Yes, often times during the day lift 50 kg ( 110 lbs), or more.

b. Yes, I lift from 20 to 50 kg loads (44 – 110 lbs) during my usual work day.

c. Yes, I lift up to 20 kg (44 lbs) during my usual work day.

d. No, I rarely or never lift anything heavy during work.

20. What are the physical conditions like in your vehicle cabin?

a. I have good shock absorbers and isolation. I don’t usually feel much vibration nor gases/fumes.

b. I have poor shock absorbers, but good isolation. I feel vibration but not much gases/fumes

c. I have good shock absorbers but poor isolation. I don’t usually feel much vibration but I do feel gases/fumes because the isolation is poor.

d. I have poor shock absorbers and poor isolation. I feel vibration and also gases/fumes.

22. Do you drive under specially hazardous conditions (check all answers that apply)

a. Yes, I carry flammable/explosive material in my vehicle.

b. Yes, I drive along winding, narrow roads

c. Yes, I face threat of violence from passengers

d. Yes, for another reason(s): ______________________________________________

e. No, I face ordinary traffic conditions, but no special hazards.

23. Have you even had an accident or been injured (including assault) at work?

a. No

b. Yes, only of a minor nature

c. Yes, I have had one or more serious accidents or have suffered serious physical harm at work:

Please briefly describe all serious accidents or injuries

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________

56. Belkic, K., P. A. Landsbergis, P. Schnall, et al., Psychosocial Factors: Review of the Empirical Data among Men, in The Workplace and Cardiovascular Disease Occu- pational Medicine: State of the Art Reviews, Schnall, P., K. Belkic, P. A. Landsbergis, and D. Baker (eds.), Hanley and Belfus, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 24-46, 2000.

60. Vahtera, J., M. Kivimaki, J. Pentti, et al., Organisational Downsizing, Sickness Absence, and Mortality: 10-Town Prospective Cohort Study, British Medical Journal, 328:7439, p. 555, 2004.

A Day in the Life of a San Francisco Municipal Trolley Car Driver:

ON A SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC TRANSPORT LINE:

Burden and consequences upon the human operator Karen Belkic, M.D., PhD, Peter Schnall, M.D., MPH

Operating a motor vehicle in the city is an activity not unfamiliar to most of us. Yet, the toll which this activity takes upon the human nervous system and target organs is, to say the least, under-appreciated in daily life. Try to imagine that rather than at most a couple of other known persons sitting in one’s car during this undertaking, one were responsible for transporting thousands each day via narrow, hilly streets, facing innumerable obstacles and under inexorable pressure to keep to a strict schedule, and that the slightest accident could result in injury to a passenger and might even put one’s job in question. And also imagine that rather than at most a few hours of this activity per day, this consumed eight or even more hours daily for five or more days in a row. These and many, many more stressors comprise the everyday experience of the San Francisco urban transport operators, who encounter problems specific to their city, but also in many ways, exemplify the difficulties which transit operators face in just about any metropolitan center which comes to mind.

On July 10, a group of us from the California Focused Study Group, had the opportunity of gaining a deeper insight into some of these difficulties and perils, during a “narrated” ride along San Francisco’s Line 22. We were privileged to have a veteran transit operator talk us through the mental processes which were taking place while the actual driver proceeded to perform the job. This perspective was complemented by Dr. Birgit Greiner’s observational methods to measure the barriers, obstacles, restrictive time binding and other stressors of urban transport operators.

Danger-Threat of Violence

While varying in degree from one urban center to another, danger and threat of violence is a common and major stressor for this occupational group. The transit operator is vulnerable to violent attack at any moment; there are frequent reports of the driver being robbed at knife or gunpoint. The enormous social problems of urban society are often manifested in hostile acts directed against the transit operator. Carrying cash and transfers increases vulnerability.

Besides physical danger, frustrated persons often verbally vent their rage upon the transport operator. They may complain about the bad conditions in the vehicle itself, about which the driver is only more than well aware. The urban mass transit operator has, de facto, to be a kind of psychologist-to anticipate and handle all kinds of people and their troubles, and to devise coping strategies to minimize the disruption from these complaints.

On the other hand, interaction with the public is not only one of the major tasks of the mass transit driver, it also is frequently a source of satisfaction and gratification. Thus, suggestions for constructing compartments to separate the operator from the public in numerous settings including San Francisco, have met almost universally with opposition. The sentiments expressed were that this would feel like “cage” and create a sense of isolation and alienation. One, more human way out of this dilemma has been suggested by Drs. Kompier and DiMartino, i.e. that on certain lines, high-risk transport calls for two transport professionals on the line, instead of one. This proposal has been resisted by the companies because, they say, it would cost too much.

Time pressure

Inexorable time pressure is the modus vivendi of the urban transport operator. One’s life becomes governed by the clock, and life is measured in time units of minutes. Waking for the morning rush hour passengers, often means rising at very early hours, sometimes two or three A.M. Scrupulously punctual drivers, fearful of not hearing the alarm, have reported to sleep lightly or not at all in anticipation of this early, strictly-defined awakening time. Running late, often not the fault of the driver, will compromise or eliminate the already short rest break which is scheduled usually at the end of the line. If the schedule is more severely compromised, some other kind of punitive measure may be taken. The driver is continuously pressing to catch-up with the schedule.

Dr. Greiner calculated that objective barriers took at least thirty extra minutes for nearly half of the four-hour work segments which she and her colleagues studied. The late Dr. Bertil Gardell eloquently described the fundamental conflict faced by urban mass transit operators: keeping on schedule versus providing to the immediate, specific needs of the public. This means not only answering questions, but also many other services, most notably, taking the extra time to accommodate the disabled and elderly.

Vigilance and avoiding accidents: Doubly burdensome for professional drivers

Even under the most ideal of circumstances, all driving requires high level vigilance to avoid accidents. The driver must continuously follow a barrage of incoming signals, to which he or she must be prepared to rapidly respond, whereby a momentary lapse of attention, or even a seemingly slight error or delayed response could have potentially disastrous consequences. For the urban transit operator this burden is much greater than for an amateur driver. For example, he or she must watch right-left-right-left before making any move, whereas the amateur driver usually makes just three visual direction shifts. An eye must be kept open for oncoming and exiting passengers and anyone at the side of the curb. There is a need to watch on the right far more than for amateur drivers. This can be one of the contributing factors to the high rate of neck and other spinal pain among professional drivers, which has been shown to be related to number of years in the occupation (witness the previously mentioned worn-down right side of the seat).

Furthermore, in situations for which an amateur driver would brake (or quickly change lanes or otherwise make some rapid maneuver), the urban mass transit operator must think about the fact that people are standing, there are frail passengers, or someone may be unsteady on his or her feet, and must try to maneuver accordingly. These dilemmas are obviously not always resolvable. If someone falls inside the vehicle, the transit operator is held liable. It should be noted that any one can stagger onto the bus, be unstable on his feet, etc. requiring yet extra vigilance for the transit operator. The biggest worry is always about an accident, whether big or small. Even a seemingly trivial accident may result in injuries to passengers.

Don’t they just get “used to it”?

An easy assumption to make would be that with experience and time on the job, a city transit operator will adapt to these conditions, difficult as they may be. And it is true that the acquired coping skills and knowledge of a seasoned professional driver are irreplaceably valuable assets, without which it would be practically impossible to continue in this line of work. There is a high turnover rate among urban mass transit operators, such that those who stay on the job for ten or more years are a highly selected group.

However, a heavy price accompanies these years on the job. The very skills which get the driver through a working day are, in fact, a quiet displacement of the burden onto his or her target organs: the heart, the blood vessels, the gastrointestinal tract, the musculoskeletal system. It has been shown both in laboratory simulation and field studies that the experienced drivers who silently cope and seemingly automatically handle the continuous barrage of potential dangers and who toughly deny how difficult this work is, are those who show the most dramatic blood pressure and electrocardiographic responses to these threatening stimuli of the traffic environment. Reviews of the literature show that professional drivers are second to none as an occupational group at risk for hypertension and ischemic heart disease and that these diseases occur at a relatively young age. Several studies of heart attack patients under the age of forty report a marked overrepresentation of professional drivers, up to 40%, in some series. The published papers showing a high risk among this occupational group for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders and/or peptic ulcer disease come from various parts of the world: from Europe, the U.S., Latin America, East Asia and the Indian subcontinent. A strong relation between number of years on the job and/or number of daily hours behind the wheel have been found in many of these studies.

The terrible human toll taken by these diseases, coming at an early adult age, also translates into enormous economic costs: absenteeism, disability and early retirement. It is unusual for a mass transit operator to retire at term in any city. In the Netherlands, for example, the average age of retirement for city bus drivers is 48 and is usually disability-based, with only 12% working until the normal retirement age of 60.

Introduction to Work Organization

“Most people spend the majority of their waking hours at work and commuting to and from work. The way work is organized—the number of hours spent working, what hours of the day we work, the pace and intensity of work, how we feel about our jobs (e.g., whether we have or do not have employment security, whether our jobs provide us opportunities for skills development and growth), our social relationships at work—can affect our health.”

Schnall PL, Dobson M, Rosskam E, Editors Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences, Cures. Baywood Publishing, 2009.

A Brief Introduction to Job Strain

Peter Schnall M.D., M.P.H.

Research conducted since the end of WWII into the causes of hypertension and coronary heart disease has identified a number of important risk factors that contribute to the development of these illnesses such as excessive caloric and fat intake leading to obesity and elevated blood cholesterol, cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, and diabetes, all of which contribute to atherosclerosis. Unfortunately, the cause(s) of high blood pressure have proven more difficult to identify, though being overweight has long been recognized as a risk factor for hypertension. Recently, attention has focused on the workplace as a potential source of stressors that might contribute to the development of hypertension.

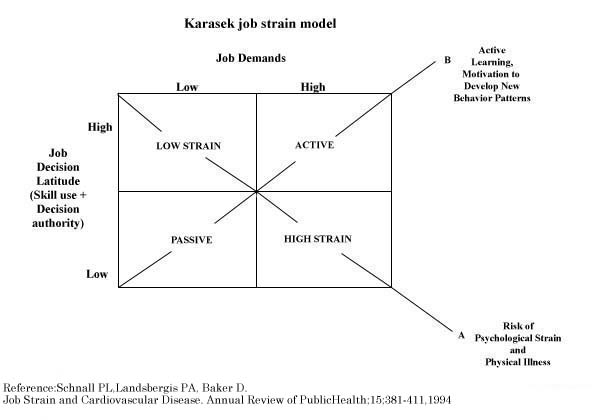

A number of specific stressful working conditions, such as repetitive work, assembly-line work, electronic monitoring or surveillance, involuntary overtime, piece-rate work, inflexible hours, arbitrary supervision, and deskilled work, have been studied. Over the last 15 years, a new model of job stress (see figure) developed by Robert Karasek has highlighted two key elements of these stressors, and has been supported by a growing body of evidence. Karasek’s “job strain” model states that the greatest risk to physical and mental health from stress occurs to workers facing high psychological workload demands or pressures combined with low control or decision latitude in meeting those demands. Job demands are defined by questions such as “working very fast,” “working very hard,” and not “enough time to get the job done.” Job decision latitude is defined as both the ability to use skills on the job and the decision-making authority available to the worker. In some recent studies, this model was expanded to include a third factor – the beneficial effects of workplace social support. While there are a variety of models of “job stress,” the “job strain” model emphasizes the inter-action between demands and control in causing stress, and objective constraints on action in the work environment, rather than individual perceptions or “person-environment fit.” Karasek’s model emphasizes another major negative consequence of work organization;: how the assembly­line and the principles of Taylorism, with its focus on reducing workers’ skills and influence, can produce passivity, learned helplessness, and lack of participation (at work, and in the community, and in politics). The “job strain” model (see figure) has two components – increasing risk of heart disease following arrow A, but increasing activity, participation, self- esteem, motivation to learn, and sense of accomplishment following arrow B. Thus, this model provides a justification and a public health foundation for efforts to achieve greater worker autonomy as well as increased workplace democracy.

Considerable evidence exists linking “‘job strain’” to hypertension and coronary heart disease. Over the last decade more than 40 studies on “job strain” and heart disease and 20 studies on “job strain” and heart disease risk factors have been published throughout the world providing strong evidence that “job strain” is a risk factor for heart disease1. Of the eight studies where an ambulatory (portable) blood pressure monitor was worn during a work day, five showed strong positive associations between “job strain” and blood pressure, while three others provided mixed results. Since Because ambulatory blood pressure is both more reliable (since there is no observer bias and the number of readings is greatly increased) and more valid (since blood pressure is measured during a person’s normal daily activities including work) than casual measures of blood pressure, we feel confident in placing more emphasis on the ambulatory blood pressure results.

The issue of job stress is of utmost importance to the public health community and working people. The economic costs of job stress in general (absenteeism, lost productivity) are difficult to estimate but could be as high as several hundred -billion dollars/ per year (2, p. 167-8). Most importantly, there is the potential for preventing much illness and death. More than 50 million Americans have high blood pressure, and, in 95% percent of cases, the cause is unknown. While estimates of the proportion of heart disease possibly due to “job strain” vary greatly between studies, Karasek and Theorell (5, p. 167) calculate that up to 23% percent of heart disease could potentially be prevented (over 150,000 deaths prevented per year in the U.S.) if we reduced the level of “job strain” in jobs with the worst strain levels to the average of other occupations.

1 Schnall PL, Landsbergis PA, Baker D. Job Strain and Cardiovascular Disease. Annual Review of Public Health; 15:381-411,1994.Schnall PL, Landsbergis PA, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG. Job Strain and Hypertension.

2 Karasek RA, Theorell T. 1990. Healthy Work. New York: Basic Books

21 Workplace Benefits That Are Rapidly Disappearing

Traditional pension plans, paid family leave, and even the company picnic are all on the decline. Employers have significantly cut many of the benefits they offer to workers over the past five years. Some 77 percent of companies report that benefits offerings have been negatively affected by the slow pace of recovery, according to a Society for Human Resource Management survey of 600 human resources professionals. “The two biggest areas where cuts have come have been in health care and retirement because that’s where costs have increased the most,” says Mark Schmit, research director of the Society for Human Resource Management in Alexandria, Va. Here is a look at the workplace perks that have significantly declined since 2007.

Traditional pension plans. Traditional pensions were offered at 40 percent of the companies surveyed in 2007. Now just 22 percent of firms provide access to a retirement plan that guarantees payments for life. More commonly offered retirement benefits include 401(k)s and similar types of retirement accounts (93 percent) and Roth 401(k) accounts (31 percent). However, the proportion of companies offering a 401(k) match declined from 75 percent in 2008 to 70 percent in 2011.

Retiree health care coverage. The proportion of companies offering retiree health insurance declined from 35 percent in 2007 to 25 percent in 2011, SHRM found. “Retiree medical plans are costly and the costs have changed over time due to factors outside the employer’s control,” says Stephen Parahus, a Towers Watson consultant. “More often than not new employees are not on a path that is going to earn them a subsidized employer benefit when they retire.”

Long-term care insurance. Just over a quarter (29 percent) of employers provide long-term care insurance for workers, down from 46 percent in 2007. Even fewer employers offer access to an elder care referral service (9 percent), a significant decline from the 22 percent of firms that offered this benefit five years ago.

Health maintenance organizations (HMOs). The number of companies with HMOs decreased from 48 percent in 2007 to 33 percent today. Preferred provider organizations (PPOs) are much more common, with 84 percent of companies offering this type of health insurance plan.

Paid family leave. A third of companies offered paid family leave in 2007, but now only a quarter of companies provide paid time off for births, deaths, and other significant family events.

Adoption assistance. Adoption assistance is another waning employer benefit, with just 8 percent of companies helping with adoption costs, down from 20 percent five years ago. Foster care assistance also declined significantly from 10 percent of companies in 2007 to only 1 percent in 2011.

Professional development opportunities. Don’t count on your company paying for you to attend an annual conference or symposium this year. While nearly all (96 percent) companies paid for professional development opportunities in 2007, only 87 percent will in 2011. The proportion of employers offering mentoring programs also decreased from 26 percent 5 years ago to 17 percent this year. “Work development is one of the things that helps train and recruit employees and can only be temporarily cut,” says Schmit. “We see dips in it during recessionary times and then we see it come back following those recessionary times.” Companies have also been cutting back on their subsidies for education expenses. The proportion of firms offering undergraduate and graduate educational assistance has declined by 10 and 11 percentage points respectively since 2007.

Life insurance for dependents. About half (55 percent) of companies provide life insurance for children and other dependents, down from 65 percent in 2007

Incentive bonus plans. Bonuses for executives are also on the chopping block. Incentive bonus plans for high-level employees are currently offered at half of the companies SHRM surveyed, down 10 percentage points since 2007.

Contraceptive coverage. Nearly 74 percent of employers provided coverage for contraceptives in 2007, a proportion that has since declined to 69 percent.

Casual dress day. Many people will need to take jeans out of their office attire rotation. Only about half (55 percent) of employers say they encourage or allow employees to dress casually one day per week, down from 66 percent in 2007. “Companies are focused on cutting out any of the extra kinds of things that might distract from their focus, even those programs that don’t cost anything,” says Schmit.

Legal assistance. One in five companies provides legal assistance or services to workers, down from a third of employers five years ago.

Sports team sponsorship. Your company may not renew its sponsorship of a local little league team next year. Only 17 percent of employers currently sponsor sports teams for workers or their families, a significant decrease from the 29 percent of companies that did so in 2007.

Executive club memberships. While about a quarter (24 percent) of companies subsidized executive club memberships for certain workers in 2007, now only 14 percent continue to provide this perk.

Relocation benefits. Relocating to a new place for a job often causes an employee to incur a variety of new expenses. Some companies step in to help finance some of the costs of the move. However, employers have significantly cut back on temporary relocation benefits, location visit assistance, and spouse relocation assistance. And only a small proportion of companies continue to offer to pay a cost-of-living differential (10 percent) or provide assistance selling the previous home (9 percent). “Instead of moving people to new facilities, companies might have them work as remote workers or take on a different style of work,” says Schmit.

Help purchasing a home. Fewer companies now aid workers with their home purchases. The proportion of companies offering mortgage assistance has declined from 12 percent in 2007 to 3 percent today. Company-provided down payment assistance and rental assistance also declined significantly over the 5-year period.

Travel perks. Employers have cut back on the travel-related perks they will subsidize for employees including travel planning services (down 13 percentage points), paid long-distance calls home while on business travel (down 17 percentage points), travel accident insurance (down 9 percentage points), and paid dry cleaning while traveling for work (down 9 percentage points).

The company picnic. Many firms are cancelling the company picnic, and not due to rain. Only about half (55 percent) of firms scheduled a company picnic in 2011, down from 64 percent in 2007.

Rewards. Company-wide rewards programs for certain lengths of job tenure with the company (down 16 percentage points) and noncash rewards for performance (down 11 percent) have both been reduced or eliminated at many companies.

Company-purchased tickets. Season tickets to the local sports team or theater that are shared by employees are now only offered by about a quarter (26 percent) of employers, a considerable decline from the 42 percent of firms that provided workers with subsidized event tickets five years ago.

Take your child to work day. Many companies no longer encourage workers to bring their children in to spend a day at the office. Only a quarter of employers continue to participate in take your child to work day activates, SHRM found, down from over a third in 2007.